They are large rafts that drift thousands of kilometres across the ocean surface, moving with the currents in an otherwise featureless marine environment. Tracked by satellites, the rudimentary floats – which may also be outfitted with long, submerged tails of netting -- are used to attract schools of fish that can be scooped up by industrial tuna fishing vessels.

Known as drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs), they were introduced into commercial fisheries in the 1990s to produce 'dolphin-safe' tuna, but have themselves become so prolific that they pose their own environmental risks.

Now, a comprehensive study by �°������ϲʿ��� researchers details their impacts on a global scale for the first time, surprising even the researchers quantifying their abundance.

We found that these devices have drifted through at least 37 per cent of the global ocean — an area as large as all inhabited continents combined

"We found that these devices have drifted through at least 37 per cent of the global ocean — an area as large as all inhabited continents combined. Yet most people have never heard of dFADs because tuna fishing occurs mostly in the tropics," lead author Laurenne Schiller, a postdoctoral research fellow at �°������ϲʿ��� and Carleton, says of the study published in Science Advances.

"Our results demonstrate that the cumulative environmental footprint of dFADs reaches far beyond tuna fishing grounds and remains inadequately mitigated at the global scale."

Growing concern

The researchers, including those from the Manta Trust, estimate that 1.4 million devices were released between 2007 and 2021 and were used to help catch nearly one-third of the world's tuna. Tuna harvesters in eastern Canada don't tend to use dFADs, which are more often deployed in the Pacific.

The study also shows that lost devices — made from natural or synthetic materials — have washed ashore in more than 100 coastal countries, contributing to marine pollution, ensnaring other species and damaging coral reefs. More than 90 per cent of some tuna species are not yet mature when caught because smaller fish are more likely to seek shelter under the raft.

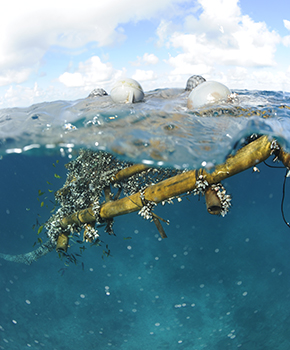

In many cases, devices are abandoned at sea. (Guy Stevens/Manta Trust)

Devices pose entanglement risks to marine life. (Alex Hofford/Greenpeace)

The authors also make clear that scientists, regulators and the fishing industry have been expressing concern about the growing use of dFADs for over 20 years after fishing practices changed from targeting free-swimming tuna schools to catching fish associated with floating objects.

Commercial use of the devices was inspired by the observation that fish seeking a protective cove tend to congregate around floating natural flotsam, such as logs or other debris. They have since become a key piece of gear for different tuna fisheries, including yellowfin, bigeye and skipjack, the latter being the main source for canned tuna products globally.

Monitoring use, retrieving gear

When outfitted with a global positioning system (GPS) transponder, a dFAD raft can be deployed from a vessel and then located weeks to months later after drifting with prevailing currents and aggregating fish.

"Because the ocean is all connected, there are no boundaries for dFADs in their global travels, and their impacts are often felt far from where they were initially deployed. We need to consider how many devices can be in the water at once and making sure they all get retrieved," says senior author Boris Worm, a marine ecology professor at �°������ϲʿ���.

Drifting fish aggregating devices come in many shapes and sizes, but all are designed to make tuna easier to catch. (Jace Tunnell)

Tropical tuna fisheries are managed through four Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, or RFMOs, and progress to address concerns has historically been slow but is increasing. Only in recent years has the use of netting been curtailed in an effort to reduce the high levels of bycatch of other marine life, such as sharks and sea turtles, and there are no limits on the total number of devices a company can deploy annually.

Transparency and accountability are also major problems, according to the study, which calls for better labelling of dFADs so that any damage they cause can be traced back to a fishing vessel or company. In 2026, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission will be the first RFMO to implement a dFAD registry for all devices used in its waters, with both the buoy and the dFAD raft bearing unique identifiers that can be traced back to the deploying vessel.

It would also help to identify responsible fisheries that are adhering to the conditions for Marine Stewardship Council sustainable seafood certification, a coveted eco-label held by most tuna fishing companies.

Minimizing ecosystem impacts

The authors show that many fisheries that use dFADs have recently been certified, but most have unmet conditions related to minimizing ecosystem impacts.

"Programs like the MSC can really motivate companies to improve their practices, but it’s also important that this improvement is continuous and doesn’t just end with certification," says Dr. Schiller. "In the case of dFAD tuna fisheries, many companies still have a lot of work to do and consumers should be aware of that."

Most [devices] are deployed by a few large companies from wealthy countries, but their effects are felt across some of the world's least developed island nations

The authors are hopeful that progress can be made and have documented comprehensive management measures that have been proposed or are already implemented, to lessen the impacts of this fishing method.

"Most dFADs are deployed by a few large companies from wealthy countries, but their effects are felt across some of the world's least developed island nations with little capacity to address the damage that is caused," says study co-author Nidhi D'Costa, a fisheries researcher from Bangladesh now working for the Manta Trust.